FJK 023

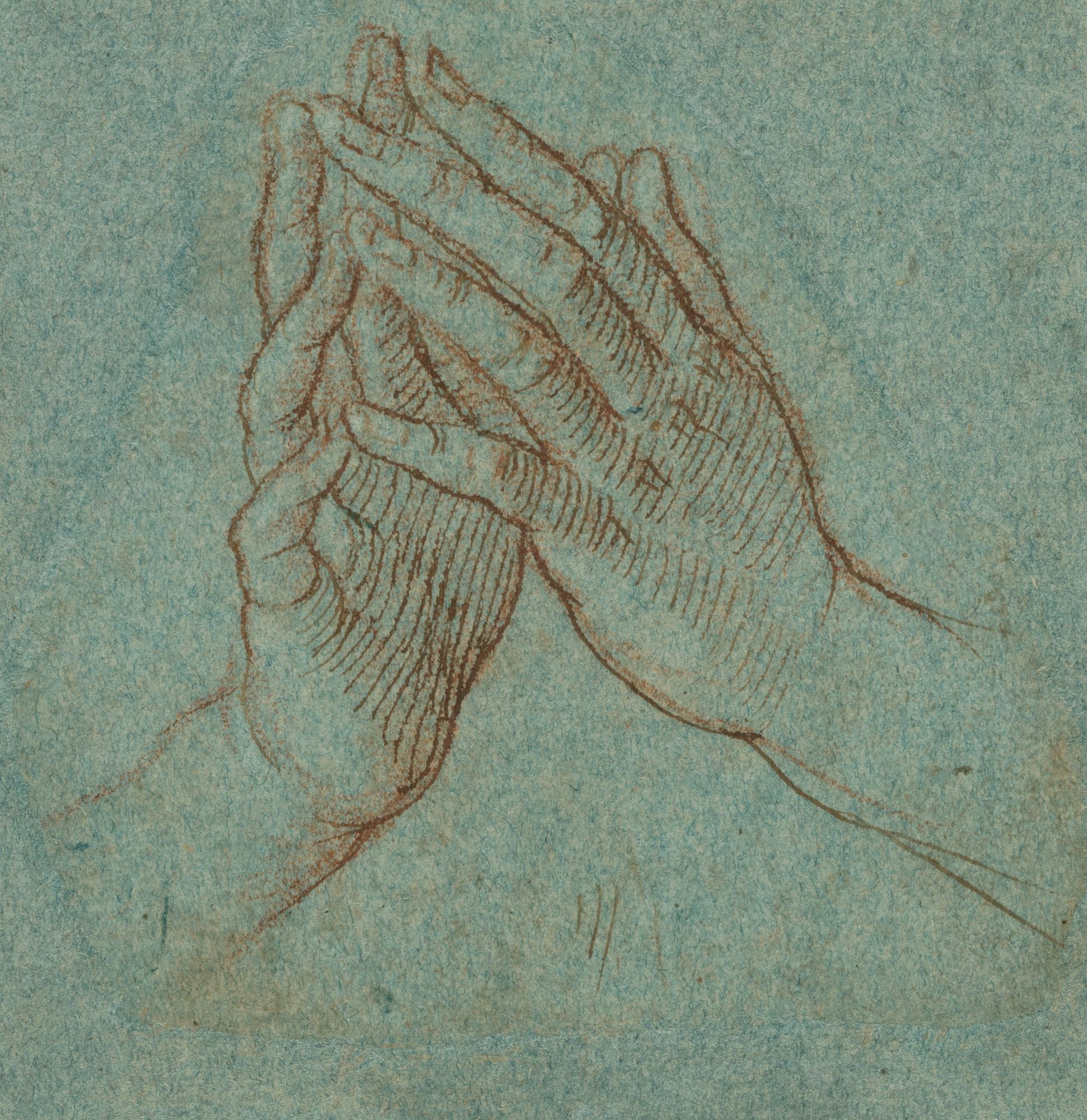

Carpaccio Vittore (Italian, Venice 1460/66?–1525/26 Venice)

Study of Hands in Prayer

Date unknown

3 15/32 × 3 35/64 in. (88 × 90 mm)

Medium

Red chalk, pen and red-orange ink on blue paper glued onto old ivory paper support

Certificate

Letter from R. W. Rearick, sent by fax, dated March 12, 2002

Origin

Private Collection, Switzerland

Jan Krugier Collection, Monaco (acquired in September 2006), JK 6685

Jan Krugier Foundation

Bibliography

Munich, Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Das Ewige Auge - Von Rembrandt bis Picasso. Meisterwerke aus der Sammlung Jan Krugier und Marie-Anne Krugier-Poniatowski, 2007, p. 60, no. 22, color ill. p. 61.

Notes

This small but deliberately controlled study might not, at first glance, sinke a familiar note among Carpaccio’s secure drawings, but it does, in fact, occupy a key position in the reconstruction of his first years of activity. Contrary to the general belief that he was born around 1455, a date that would have placed his early works twenty years prior to his first documented picture of 1490, his birth is more probably to be fixed in 1468 circa, and his apprenticeship must have begun in the shop of Gentile Bellini in 1481 on that artist’s return from Constantinople. When, that same year, he assisted both Gentile and his half-brother Giovanni in the execution of murals in the Palazzo Ducale in Venice, he was simultaneously assigned the task of painting replicas and variants of Giovanni’s popular smaller devotional compositions. His youthful efforts were signed with the older master’s name, a normal practice since the signature was a sort of imprimature that guaranteed that the work issued from the Bellini shop. Just before 1486, Giovanni painted a Madonna in Adoration of the Christ Child (lost, a shop replica in London, National Gallery, no. 2901), a composition that was immediately replicated by still other of the apprentices there (formerly Florence, Contini Bonacossi collection, Florence, Harvard, Villa I Tatti, Berenson Collection; etc.). With Bellini’s painting probably still before him in the shop, he choose a fine sheet of blue paper (here remarkably well preserved in its fresh color) and set about drawing the Madonna’s hands in a prayerful position that presents them as somewhat more vertical and as seen closer to a frontal position. Using a pointed stick of red chalk, which he complemented with an orangy-toned ink line that adds a clear, tensile pen contour that bespeaks an already secure grasp of organic anatomical structure, he modelled the chiaroscuro in carefully modulated parallel shading strokes. Its clear regularity still echoes the rigorous use of line in the drawings of Andrea Mantegna, long since departed to Mantua but by way of engravings still a forceful presence among Venetian draftsmen. The choice of this medium at once declares his independance from Giovanni’s approach to drawing. Bellini, like the great majority of Venetian draftsmen, never used red chalk which was in large measure a favored Lombard material, nor do his nervously pictorial sketches convey this degree of discipline. This study is clearly that of an ambitious young draftsman anxious to demonstrate his professional expertise. Carpaccio would use this combination of red chalk and ink for quick compositional explorations throughout his career, albeit later in a far more jagged and rapidly applied stroke. His range of approach and medium would become remarkably wide for a Quattrocento draftsman, but similar studies of detail are rare at any point in his career. Parallel effects may be seen in a recently discovered sheet (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, no. 87.GG.8) with studies for the Madonna (Venice, Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavone) of about 1502. At this point you may well ask why there is no reference to two sheets of studies that relate to Carpaccio’s polyptich altarpieces in Sant’Anastasia cathedral in Zara, almost always dated to ca. 1487, or the altarpanels at Grumello de’Zanchi, equally placed early in his career. The reason is that the sketch of the former has a study on its verso for the 1493 Martyrdom and Funeral of Saint Ursula (Venice, Gallerie dell’Academia) and the latter a figure of Christ for the Blood of the Redeemer altarpiece (Udine, Museo Civico), a painting signed and dated 1496. In this instance the legendary “Popham’s law” that a study on the verso is almost always by the same hand and probably of the same period as the recto seems fully justified.

With this, and doubtless other studies based on the Bellini Madonna, in hand Vittore set about painting his own version of this type in a delicate picture (New York, private collection; exhibited at the Berry-Hill Gallery there in 19..). The angle of view of the hands is virtually the same as in the drawing, the carefully calculated play of transparent shadow leads to the chiaroscuro of the picture, and space and line are nearly identical in both. Compare, for example, the area and contour just below the palms of the hands. In short, it seems clear that the present study is Carpaccio’s preparation for the New York picture; that it carries Giovanni Bellini’s name on the cartello means simply that Vittore had not yet matriculated as an independant artist.

Using this study developed from the Bellini Madonna in preparation for his own New York Madonna, Carpaccio now began a variant treatment in reverse, preparing a panel with a coat of ivory gesso. He then took his completed cartoon and pricked its contours for transfer to the panel by pouncing, a technique of stumping carbon dust through the minute holes to leave a guide on the panel for its execution in tempera paint. Since this process of transfer usually damaged the cartoon, he was careful to draw the Child in the cartoon with a brush and chiaroscuro technique adapted to reproduce the finished effect of a painting. This ricordo survives today (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, no. ) with the Child’s legs reproduced higher and to the left since his paper proved too small for the full figure. Finally, if we turn the Ashmolean sheet over we find on its verso a typical Carpaccio sketch which affords the direct connexion with a small pair of panels that, unlike the preceeding material which is quite new to Carpaccio studies, are almost universally accepted as by Carpaccio, the Saint Catherine of Alexandria and the Saint Veneranda (both Verona, Museo del Castelvecchio), works datable just a bit later. In the drawing the attributes of the martyr saint have not yet been developed, but there can be little doubt that Vittore picked up his ricordo to adumbrate on its verso his idea for the Saint Catherine. His project for the Madonna was not destined to be brought to completion. Following the dots left by the spolvero transfer, he drew with a stick of charcoal the outlines of the figures but then, for unknown reasons, he abandoned the project leaving the gessoed panel with its underdrawing. Perhaps Bellini was not pleased to see his composition in reverse; he was still the boss who assumed responsibility for such pictures. Only several centuries later did some enterprising art dealer have a faked Bellini painting cover Vittore’s start, a falsification that was removed when the Madonna entered the Fogg Art Museum, of Harvard University with the Winthrop collection. Within about two years Giovanni Bellini would undertake the organ shutters for the church of Santa Maria dei Miracoli. He painted much of the head of the Saint Peter (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) before turning the project over to his earstwhile assistant who finished it, doubtless following the same sequence with the Saint Paul (lost), before undertaking the monumental Annunciation (Venice, Gallerie dell’Accademia) that constitutes his firts totally independant work.

The present Study of Hands is, therefore, together with the Ashmolean sheet, Carpaccio’s earliest known drawing, and will receive a more complete analysis in my forthcoming book, Carpaccio Studies, in which a chapter will be devoted to his drawings with a dozen or so newly identified sheets. It is my understanding that other scholars, among them Nicholas Turner, have also suggested the name of Carpaccio as the possible author in this case.

Fax by W. R. Rearick, 12/03/2002

Request for information/loan

The Jan Krugier Foundation is devoted to increasing the impact of the collection of drawings through regular loans to major exhibitions. Loan applications should include a complete presentation of the project.